Plant Histories

Students Hannah Baber and Robert Curtis, both at the University of Sheffield, have been researching the history of plants that Marnock used in Sheffield Botanical Gardens.

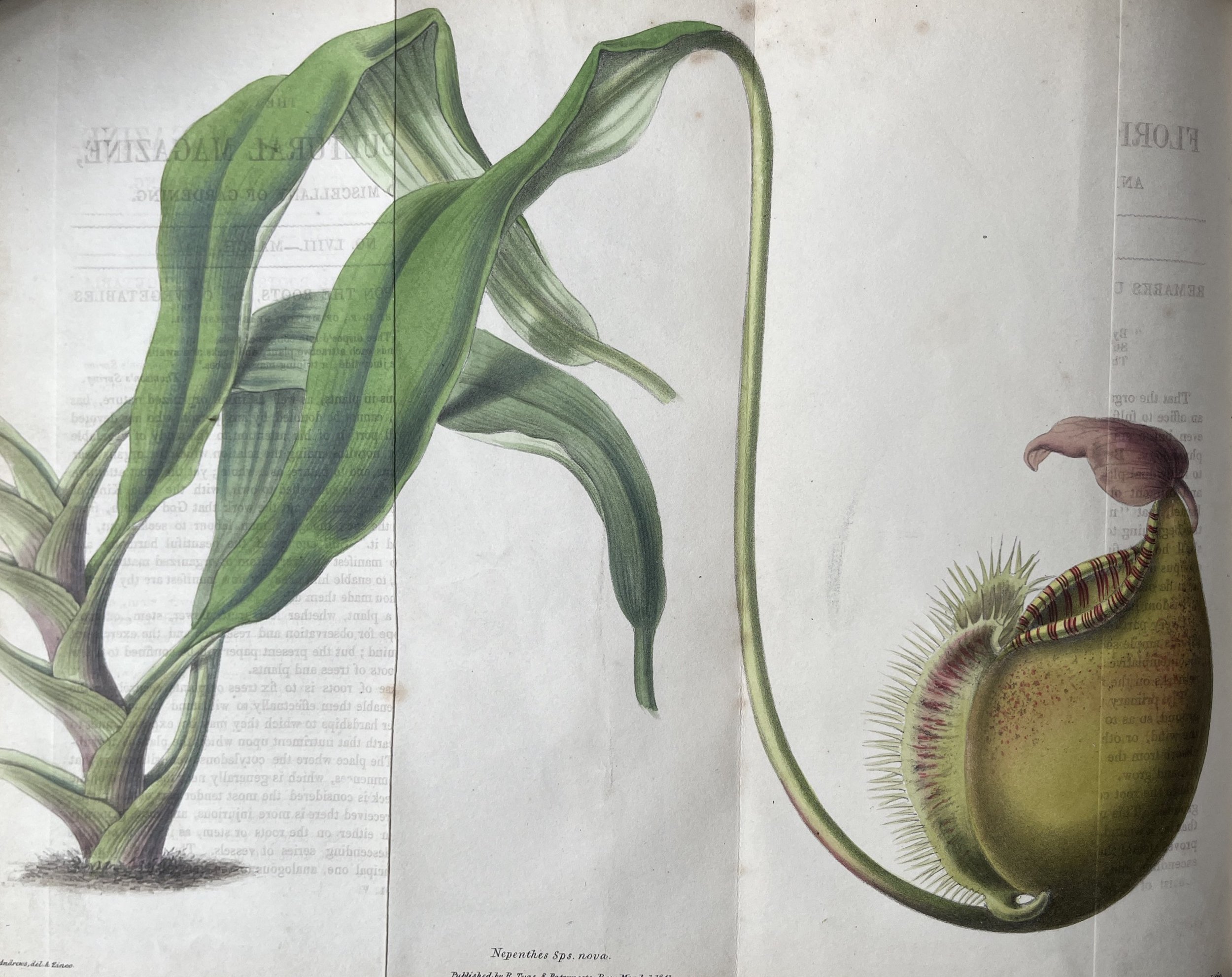

The Cavendish Banana

This appears as Musa Cavendishi in Marnock’s 1838 catalogue of plants cultivated in Sheffield Botanical Gardens. He locates it growing ‘in the small stove’.

Two banana plants (Musa species), one with fruit. Watercolour, 1846, after C. Goodall, 1842. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Musa acuminata, more commonly known as the Cavendish banana, makes up 40% of banana production worldwide. Although native to Central and Southern Asia, preferring humid tropical climates, the specific Cavendish variety descends directly from a plant grown since 1830 in the hothouse of Chatsworth House located in the Peak District, England. Its original acquisition speaks to a wider history of colonial sciences as, during the 18th and 19th century, scientists and gardeners alike showed increased interest in such "exotic” plants, bringing specimens back to England. Botany itself was fuelled by the wealth of plants available to colonial collectors through the British Empire, there were implicit ties between the Empire and botany as a science. The banana remained a popular key image of such exotism beyond these Gardens, first being put on display in 1633. It would become a symbol of the expanding colonial empire of Britain, associated closely with early use of the adjective ‘tropical’.

This English variant made its way back to its tropical origins as well as being transported to the Pacific and Canary Islands. By the 1930s, it had become the prominent cultivated variety as the Panama disease spread through other commercial varieties, and proved lethal.

Prunus dulcis (Almond)

Listed by Marnock in his catalogue as Amygdalus Communis, and located on the south side of the rose ground.

Almond plant (Prunus dulcis): flowers, fruit and seed. Coloured zincograph, c. 1853, after M. Burnett. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

The almond or Prunus dulcis has been valued for centuries for its nutrient-rich nuts that have provided a vital source of nutrition throughout human history. Historical records locate the almonds variant we know today to around the 3rd millennium BCE in present day Iran and Armenia. These almonds were later found buried in Tutankhamun’s tomb who died in 1325 BCE and would have been placed there as a means of sustaining the Pharaoh in the afterlife. The plant has also taken on many spiritual meanings, being a sign of fertility for the Greeks and that of life, rebirth and vigilance for the Hebrew people.

Flourishing in areas such as Spain, Morocco, Greece and Israel, the almond also fed and was transported by merchants travelling the Silk Road during the 1st century AD. In 1890 Van Gogh, while living in Southern France, also used the almond and its blossoms in many of his famous and beloved paintings. The almond is an example of continuity in human civilizations; we continue today to rely on the plant as a source of nutrition as we have been doing for centuries.

Catalpa bignonioides (Native American bean tree)

Listed by Marnock in his catalogue as Catalpa syringifolia, growing on the top lawns.

Catalpa bignonioides (as Bignonia Catalpa) from Afbeeldingen der fraaiste… (1802). Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by Missouri Botanic Gardens.

The Native American bean tree, originating in the Eastern USA, is prized by European botanists for its beauty. Its heart-shaped leaves emerge as gold before changing to green in the height of summer, and its bell-shaped flowers are flecked with purple and orange. Slender, bean-shaped fruit containing winged seeds emerge in autumn into winter, and this is what gives the tree its name - though the name was famously misspelt by the botanist who introduced it to Europe in 1726. He confused catalpa for the Catawba Native American people who lived near to where the tree originated, though it has nothing to do with them.

It did, however, have special significance for the Cherokee and even gave its name to Barbara Kingsolver’s 1988 novel The Bean Trees. The book is a staple of US schools, and it has the protagonist look after a Cherokee child on a journey that mirrors the “Trail of Tears”, a forced relocation of the Cherokee people by the US government in the mid-nineteenth century.

Taxodium distichum (swamp cypress)

Listed by Marnock in his catalogue as Cupressus distichia, growing in the northeast corner of the Gardens.

Taxodium distichum from A description of the genus Pinus… (1837). Image from The New York Public Library.

The swamp cypress is known for its peculiar knee-shaped roots, which rise above water to supply oxygen to its needle-shaped leaves. The oldest specimen, found in Florida, is known as ‘Big Dan’ and is said to be over 2,700 years old, though the ‘Senator’ of Florida reached 3,500 years before it was accidentally burned down in 2012. Native Americans of North Carolina used the bark of the tree to build their homes as it is both water-resistant and repels insects, while the Seminole were famous for their cypress canoes. A 1728 European expedition to survey the Great Dismal Swamp of Virginia followed the Native Americans’ example, laying the cypress bark on the ground where they slept.

Ultimately the tree reached England through botanist John Tradescant, who planted it alongside numerous other American saplings in his botanic gardens in Lambeth. This was part of a wider process of acquisition of items to be displayed in the Tradescant family’s ‘cabinet of curiosities’ known as the Ark, the first museum in Britain to be opened to the public. The Ark contained numerous items of cultural significance to the Native Americans that Tradescant obtained on his expedition, including a ceremonial deerskin belonging to the chief of the Powhatan people.